“Alright,” your friend the fighter says. “I’m going to smash down the door.”

Great. You’ve got options. In fact, you might have too many options.

If you’re using a module, there might be a piece of information somewhere that says “the doors are iron, and need a DC 20 check to smash down.” Tell your friend to hold on a sec while you check the book. No problem, not really.

If you’ve made up your own doors—fancy you—you might already know what your friend needs to roll against to get ’em down. Great.

If (and this is the most likely scenario here) your group has gone off on a deep tangent, ended up lost in the woods and trying to kick down an innocent witch’s cabin door, you’re making a ruling on the spot. Perfect, because you’re playing a game where rulings > rules, or some such non-sense, so yay, you’re doing it. You’re making rulings.

“Uhm, okay, go ahead and roll.”

“I got a 17.” You didn’t say the DC out loud before your friend rolled, but in your head, it was 16, so that’s good enough. You tell your friend. Your other friend, the one who likes verisimilitude and understanding the game world, points out that a 17 wasn’t good enough last time, and they’re confused, because these doors you’ve just described are harder than the previous doors described.

You get out your notebook, and you find a new page, and you take 10 minutes to write down DCs for every possible door the players might encounter, so you’ll always know what DC you should set when they see a door and decide that a door shouldn’t be closed any longer. It took 10 minutes, but now there’s verisimilitude, and you won’t have to make up an excuse like “oh these doors are different doors than the doors three doors back.”

Let’s say you did say the DC before your friend rolled, so everything is above-board, and your verisimilitude loving friend pointed out how much you suck, therefore letting you course correct the door DC up to a healthy 18, which your fighter friend then doesn’t pass, and now she feels cheated, because she would have made it if nothing was said. Tension brews.

Exaggerated? You’d think so, but this is happening everyday to GMs everywhere. I assume. I don’t actually know.

What if there was a better way? What if there was… a procedure? A way to set the DC of a door and so much more? In a way that made sense, and felt fair, and everyone could even get a hand in on? Maybe with a little bit of that player agency that gets tossed around in the “GM Advice” slushpiles?

Well, here it is:

The Only Way To Properly Set The Difficulty of Something, Ever, for Every Game

Step one: Get friends, play games with them, and encounter a situation where success is not guaranteed. If you’re playing The Big Game that’s easy, but this method works just as easily with The Small Game and The Indie Game. Yeah, those ones you’re thinking of are the same ones I’m referring to here.

Step two: Decide on the base DC for the entire world that’ll ride forever. I mean maybe you could tell your players that the “base DC is going up because you’ve teleported into hell or something,” that actually sounds neat, so I’m going to steal that. (My original notes didn’t have a shifting base DC, so it’s pretty neat that I can take this good idea.)

Step three: Have a sheet or something you can put on the table in front of everyone. If you’re Online, you can do this with your favorite VTT pretty easily, and if you just talk in discord, you can have a message you copy and paste or something.

We’re cribbing hard from Schema to set up the sheet, so, I guess just be aware of that? (As such: Some text is from Schema by Levi Kornelsen; used with permission.) But Schema has a cool method of resolution where the GM assigns dangers to a task, and that’s what we’re looking at here.

So, on your little DC cheat sheet (player facing) have the MAIN DC in bold front and center. Let’s call it 10.

Under that, have a few smaller bars called “Difficulty” that have new DCs under them. Let’s say you have 5, and each one increases the difficult by 3. So they’d be 13, 16, 19, 22, and 25.

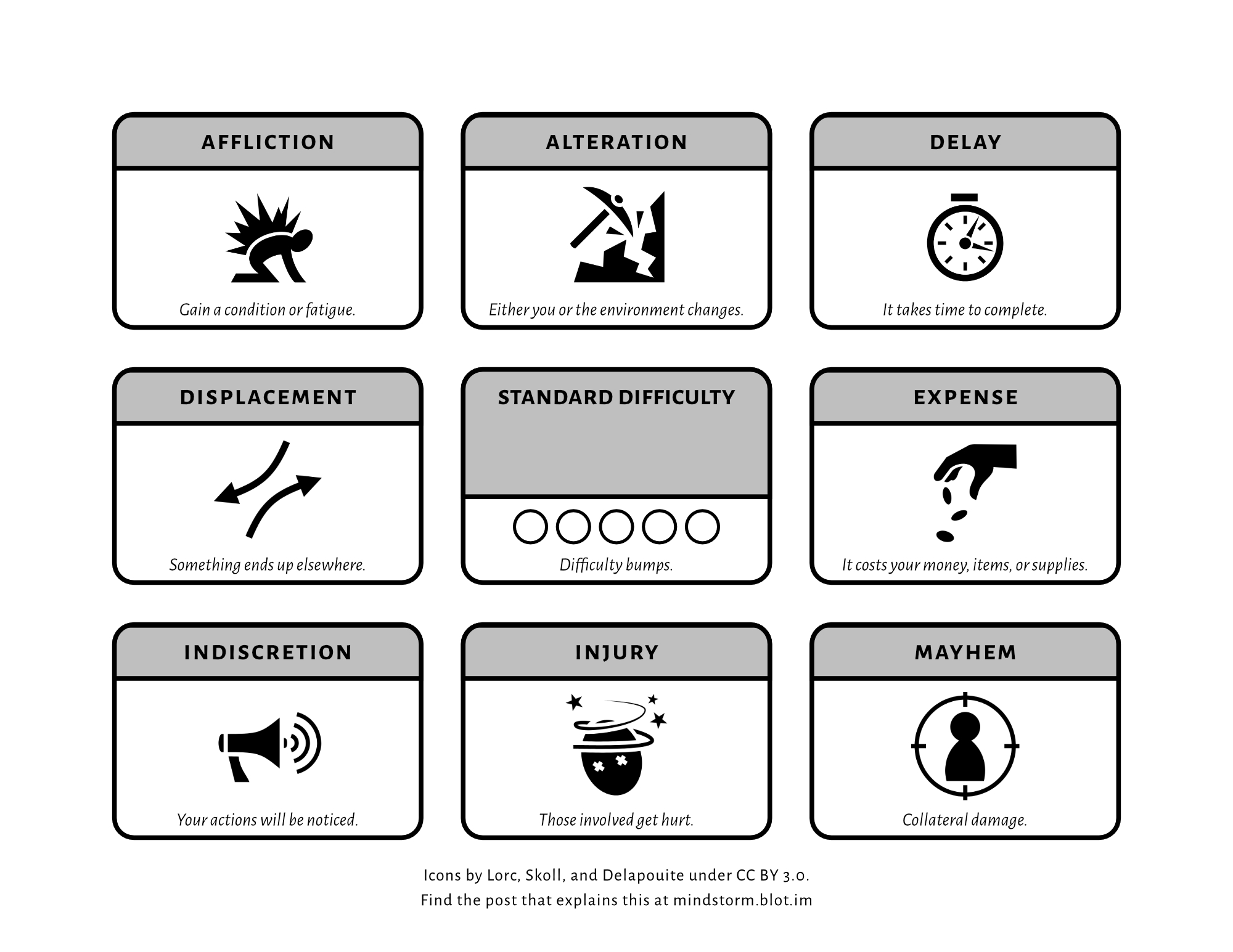

In a beautiful array surrounding the main DC, put some other cool words—like the things I’m taking from Schema. So put Affliction, Alteration, Delay, Displacement, Expense, Indiscretion, Injury, and Mayhem.

Those things, described, are:

- Affliction: You get a condition, or fatigue.

- Alteration: Something about you or the environment is changing.

- Delay: It’s goin’ take time.

- Displacement: Something is going to end up somewhere else.

- Expense: It’s going to cost you, probably an item, or supplies.

- Indiscretion: You’re loud, or flashy, or something—you’ll be noticed.

- Injury: It’ll hurt.

- Mayhem: Collateral damage.

Step four: As you take stock of the situation, put little markers or tokens or M&Ms on the sheet, saying out loud what the problems are. So, for the door example, you might put two pieces of candy on “Difficulty,” bumping it up to 16. You might also put a piece of candy on “Indiscretion” because it’s going to be loud.

Step five: Let the players finagle stuff. Your good and trusting friend might decide that being loud is bad, because that means bad things will know where you are, find you, and likely kill you. So she says, “wait, we can’t be loud right now. We’re sneaking.” Which is cool. PLAYER AGENCY, right? Everyone loves it. So you say, “okay, slide that M&M somewhere else, and tell me why.”

Neat, huh? So maybe she slides the M&M just straight over to the next difficulty spot: it’ll be harder, to try and force the door silently, but it can be done. But maybe she slides it over to delay instead? It’s not tough, it’ll just take you time.

(Sidenote: if you have delay as an option here, you need to have some kind of encounter method or system in place to make taking time to do this effective. {in fact, none of these potential options should be cop outs. If the players accept indiscretion for being loud instead of a higher DC, they’re loud, period. If there’s anything on the other side of the door, it hears them. If they choose mayhem and say “well the door is broken, that’s collateral damage, haha!” you need to smile along with them, and then explain how the load bearing part of the door also broke, so it looks like this whole hallway might come down pretty dang soon.})

Step six: Bask in the glory of being the best GM of your friend group.

Wait, I’ve Got Reservations

… and not the kind for dinner. Okay, what’s up, self?

Doesn’t this mean rolling a single check takes forever?

I mean, it probably takes about as long as it does to put M&Ms down on the paper. You’re not rolling for everything, all of the time, are you? I mean, rolls should mean something. Putting down a few candies and letting your players move them around to finagle a situation to their advantage is good, actually.

No, I’m not convinced. It’s going to take 5 minutes to roll a d20.

If you do this a few times you probably don’t even need the visual aid, you can just say out loud what the problems are, and players will finagle their own solutions.

Is this pixel bitching?

I don’t know. I don’t care.

My players are shifting around the M&Ms like they’re playing a shell game, but without the shell! What do I do?

Let them, I guess. It seems fun to me that players would shuffle things around to try and make an impossible check, well, possible. And they know the stakes! They’re the ones setting them, and they don’t even know it! Here’s a fun thing to try, that I haven’t, but just thought of: don’t even set the initial stakes, just pick up x amount of candies and put them next to the sheet, and tell the players to sort it out. They’ve got to assign all the M&Ms somewhere.

Does it have to be candy?

Yes. If the player succeeds, they get to eat it. If they fail, you get it. This advice is for future archivists stumbling on this post, way down the road, when we’re not suffering from a worldwide pandemic.

Can I just set a DC without this if I am in a hurry, or should I use this for absolutely everything?

I don’t know, why would I even think of this question? It’s a strawman’s question.

What if they try to shift the candy to something that doesn’t make sense?

Make a ruling, and tell them that doesn’t make sense. Or, think about it for a bit, and see if you can find a way for it to make sense—and it might not be in the way they were thinking!

What about all the non-d20 based games, or things like roll-under?

Just make it so that each M&M added to the “difficulty” bar makes the check harder. The other conditions can probably stay the same easily enough, I’d think?

Being you, I know you, and you’re a big practioner of the “only roll at the moment it’s important” line of thinking, right? This is incompatible with that!

Thanks self, for the self-doubt. But no, it’s not. If you’re sneaking, you roll at the moment a guard might spot you—and you just use this the same way. Toss a couple M&Ms on the difficulty if that guard is particularly alert and see what happens! The player might slide one difficulty over to displacement: they leap into the nearest window to avoid being spotted! Where the heck did they end up, though?

Or maybe they’re going to slide the difficulty over to delay: they’ll back off and try and wait this guard out. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that this system doesn’t work unless you’re using the above advice. You can’t just say “I sneak through the mansion” and roll meaningfully, you can only roll (and finagle the roll) when there’s something out there that might catch you.

Make It Harder and/or Easier, Please

Okay. After the stakes are set, you can only shift the candy around if you’re trained in what you’re doing. That might just be a narrative thing—a thief practiced in B&E knows how to pick a lock, they can shift the stakes on lockpicking.

Or, if you don’t like that: you can shift a number of candies equal to your level divided by two, or three, or four.

To make it easier, follow the same advice but allow someone trained in the task to completely remove a candy. Otherwise, they have to shift it somewhere else.

Personally, I like the shifting around, so I wouldn’t impose a difficulty or allow removing of M&Ms (except in special circumstances, see below.)

Bonus Mode: Replacement for Skill Challenges

Lots of people love to talk about 4th edition D&D, and the skill challenges it had. To put it simply, you basically had a situation described to you, and then you rolled your skills to try and accrue successes. Get x successes before failures, and you’d win the skill challenge. To put it complicated, read this.

A good friend pointed out to me that using this method, you can essentially run a skill challenge in a similar way. Doing a check this way is still only a single roll per player, but there’s a lot of discussion before the roll. I think this is a neat way to build up tension for a resolution without it requiring roll after roll after roll. This is how it works:

Describe the scene. As you describe the situation and the stakes, put down M&Ms on the auxiliary problems, explaining what happens no matter what, even if you succeed. Put down a lot of M&Ms, since this is in operation for the entire group as opposed to just a single player’s check. Tell the players what kind of check the challenge will be: if you’re using a more modern system, choose a couple of applicable skills.

Then, go around the table, and let each player describe what they do. They can completely remove and eat a single M&M each, as long as they describe how their character mitigates the problem. This can include M&Ms on the extra difficulty bumps.

Players can also take some kind of fatigue, or exhaustion, or sacrifice a piece of equipment to remove a second M&M, after the first round of picks is complete.

After two rounds are over, all players roll against the DC, using whatever skill or attribute you had already set. Unlike a traditional skill challenge, they don’t get to try and finagle a different skill or attribute to use: you’ve preset it, and they’ve had time to eat up the difficulty if they’re bad at that skill.

If the majority of players pass the check, the challenge succeeds. Any remaining M&Ms on the board are events that happen anyways, as normal.

An Example: Fleeing From The Palace

The players, being agents of pure and unbridled chaos, are in the very center of some kind of ducal palace doing things you shouldn’t do inside of a ducal palace, and they’ve been discovered. Now they need to fight their way out and back to that sweet, sweet freedom.

As they panic and try to convince themselves that they’re in the right for the atrocities they’ve committed, I pull out an entire bag of M&Ms and start putting them down.

- I put 3 M&Ms on injury and say: the guards are out for blood and they’re stab-happy.

- I put 2 M&Ms on displacement and say: two of you are going to get separated from the others in the chase.

- I put 2 M&Ms on indiscretion: you’ll get out of the palace, but they’ll see which way you’re headed.

- I put 2 M&Ms on mayhem: you’ll destroy priceless artifacts in the palace in your mad dash.

- And lastly, 3 M&Ms on difficulty, cranking it up because this is a fancy palace and it’s kind of hard to get out of those.

Lastly, I tell them what kind of check that they’ll have to beat.

For the first round, each player can eat a single M&M and describe how they mitigate that problem. On the second round, they can push themselves and take some fatigue to eat another M&M. With 5 players, that’s potentially 10 M&Ms off the board, but they’re all suffering in some way to do it.

After that, it’s a single roll from each of them (up the tension by taking Retired Adventurer’s advice and having them roll sequentially, in order from most likely to succeed to most likely to fail.)

Closing Remarks

I hope this got you thinking! You could conceivably make an entire game system with this method, and if that sounds interesting to you, I suggest you do it! At the very least, check out Schema to see it executed in a slightly different manner (in that, there’s also good augmentations you want, and you’re rolling FATE dice to cancel out the bad and pick up the good.)

Did you enjoy this post? Consider signing up to the mindstorm, my semi-regular newsletter!